Oregon Treasury’s Bet on Private Investment Undercut by Zombies

Oregon was one of the first adopters in the US of private equity fund investments in the early 1980s. In those early days, the returns were high. A couple decades later, types of private fund investments have multiplied, and the risks of these funds are ever more apparent.

There is a need now for a nimble, urgent response to the many crises caused by a changing climate, including financial crisis. The trait of private funds which is particularly problematic is illiquidity or the amount of time fund investments are tied up. Private fund contracts are typically a decade and they can be extended even longer.

The Oregon State Treasury (OST) has an especially big problem since they have invested well over half of PERS members’ retirement in private funds.

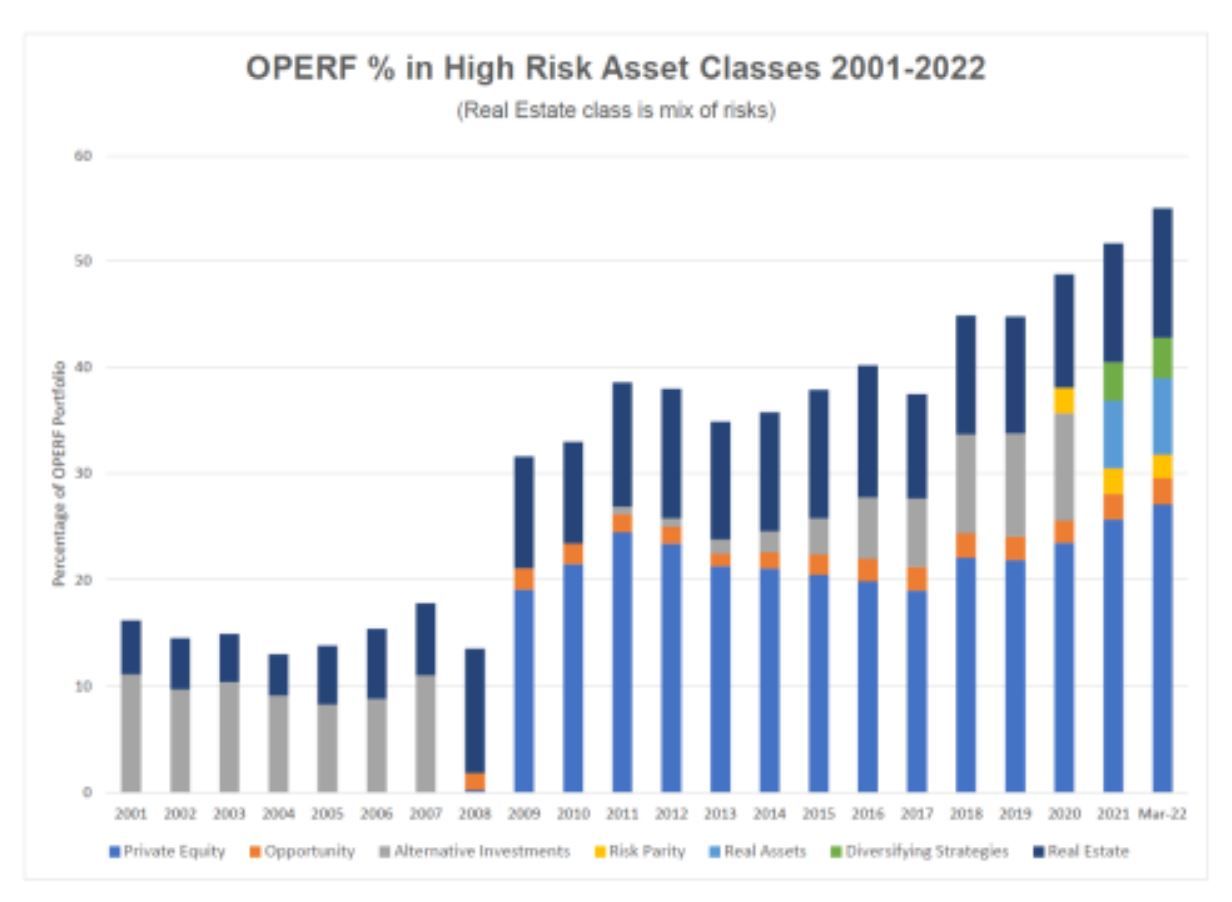

In 2009, after a severe recession and a 28% loss to the OST, private fund investment was doubled to 30%. At the time Tobias Read was elected treasurer in 2016 it was 40% – and it kept increasing. As the graph below shows, it was 55% in March of 2022.

Chart from Divest Oregon report "Oregon Treasury Private Investment Transparency Problem" (p 11)

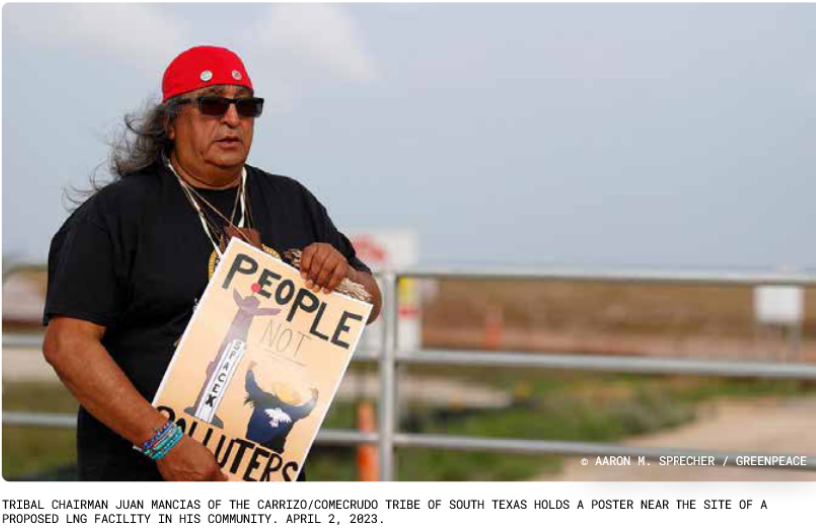

In the face of the climate crisis, and in spite of Treasurer Read pledging a year ago to decarbonize the portfolio, OST investments in fossil fuels through public and private funds continue. Lack of transparency as to OST fossil fuel investments limits the information open to the public – and to the fund beneficiaries. An investment of over half a billion was acknowledged by Treasurer Read, in a January 2023 Oregon Investment Council (OIC) meeting, as having “oil and gas exposure.” Nichole Heil of Private Equity Stakeholder Project testified in September 2023 before the OIC and noted a February 2023 $250 million investment in Natural Gas Partner (NGP)’s fund. She noted NGP’s track record: "Global Energy Monitor’s analysis concluded that from 2014-2021, NGP portfolio companies generated at least an estimated total of 97 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent or about the annual emissions of 26 coal power plants."

So the OST has locked up retirement money in private funds – and in the fossil fuel industry. And each of these actors is under stress.

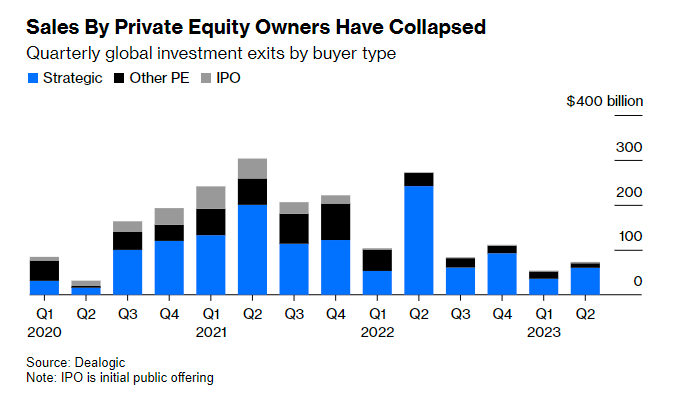

Chart from "The Private Equity Machine Will Be Tough to Unjam"

The following excerpts provide a rough summary of the article "The Private Equity Machine Will Be Tough to Unjam" (Bloomberg Opinion, 7/3/2023)

Private equity deal making faces two big problems. It is hard to value companies and work out what debt they can bear while interest rates are still moving. The biggest problem is that private equity funds haven’t been paying out much money because it has become hard to sell many of the companies they own at a time when interest rates are rising and inflation is high. Many of the companies that funds already own were loaded up with floating-rate debt before inflation became a problem. The rising cost of that debt is eating up more of their potential profits. Unless rates start to fall again, those companies are going to have to work extremely hard to generate cash and keep their heads above water before their owners can even think of selling them on. Private equity firms live to do deals, to keep raising fresh funds and turning companies over, but with sales grinding to a near halt the whole machine looks like it could be seized up for quite a while yet. That’s tough for the fund managers, their investors — and all those bankers that have come to rely so heavily on the industry for fees.

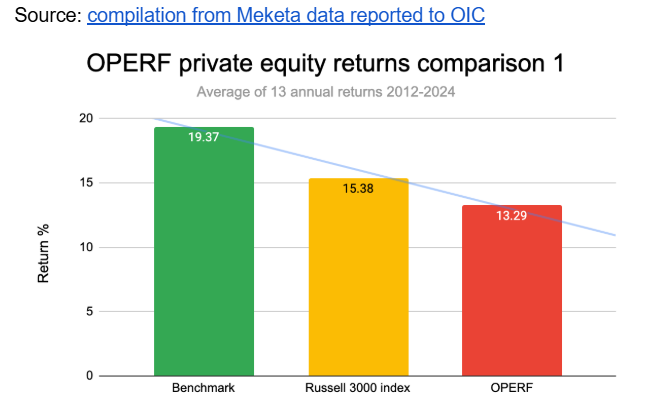

Chart from Bloomberg Weekend Reading 9/30/2023

Note: This chart includes only private investments in Oregon PERS private equity asset class.

About half of Oregon PERS’s investments are private investments, found in the private equity and several other asset classes.

The following excerpts provide a rough summary of the article: Private Equity’s Slow Carnage Unleashes a Wave of Zombies (Bloomberg 9/24/2023)

Across the $12 trillion industry, hundreds of private equity firms are lumbering on years after their funds’ intended twilight with no new fundraising in sight — a cohort that investors and regulators have dubbed “zombies.”

Many pensions have maxed out how much they can devote to the illiquid asset class. Instead, they’re steering cash to investments that are more attractive as interest rates climb. The result: Buyout firms that failed to build fresh war chests during the recent boom years of low interest rates are now finding it difficult to arrange fresh funds. The industry is on track to raise 28% less than last year, according to Bain & Co. At the same time, aging funds are finding it harder to sell out of their remaining holdings as rising borrowing costs sideline potential buyers.

Pensions and endowments can’t force private equity managers to sell. They can’t pull money from a fund without typically paying a price. Nor can they replace a manager unless there's evidence of wrongdoing. That means zombie funds can go on for years, sucking up pension managers' time and eroding returns. That’s an inconvenient counterpoint to private equity’s pitch that it can reliably take cash from teachers, police, firefighters and other civil servants and hand it back with significant returns a decade later.

For more details about private investments such as:

- What are private investments, such as private equity?

- What are concerns about private investments?

- How do private investments relate to fossil fuels?

See the Divest Oregon report "Oregon Treasury Private Investment Transparency Problem."